A Peace that Passeth Understanding

How 100,000 enemy soldiers defied orders—and revealed the power of human agency

As 2025 draws to a close, we find ourselves in a world increasingly defined by divisions that feel insurmountable. Wars rage across multiple continents. Political polarization has reached levels that make dialogue across differences seem naive at best, dangerous at worst. Our social media feeds reinforce the message daily: we are enemies, separated by unbridgeable chasms of ideology, identity, and interest.

In moments like these, when the very possibility of peace seems like wishful thinking, history offers us something more valuable than hope—it offers us evidence.

On December 24, 1914, something happened that defies our modern assumptions about conflict, tribalism, and human nature. It was an event so improbable that many dismissed it as myth, so counter to everything we think we know about war that military historians still struggle to fully explain it.

The undisputed facts are these.

From December 24-26, 1914, five months into World War I—a war that had already claimed over one million lives and would go on to kill 25 million more—an unofficial and entirely unauthorized ceasefire erupted along the Western Front. Without orders from above, without diplomatic negotiation or military sanction, along some two-thirds of the front controlled by the British Expeditionary Force, the guns fell silent.

And then something even more extraordinary happened.

Close to 100,000 men, trained and ordered to kill one another, emerged from their trenches to sing Christmas carols, share food, exchange stories, and play football together in the space between the lines.

What occurred over those three days more than a century ago seems nothing short of miraculous. Otherworldly. The kind of thing that makes us wonder if we’re reading fiction rather than history.

Yet this mass defection from the logic of war cannot be dismissed as accidental or inexplicable. If tens of thousands of men, designated as mortal enemies by their nations, could collectively choose restraint and recognition in the midst of the deadliest war humanity had yet known, then the question is not whether it happened.

The question is how.

To answer this question—as we shall see—is to understand something vital about human agency, about the incremental power of small acts of humanity, and about the conditions under which even the most entrenched conflicts can be interrupted.

Creating the Conditions: How “No Man’s Land” Became Shared Ground

It was the early months of World War I and the killing had proceeded at an industrial scale. By late November 1914, one million soldiers lay dead. To shield troops from relentless gunfire and artillery bombardment, military commanders ordered the construction of trenches along the 475-mile Western Front.

These rival trenches were dug in remarkably close proximity—often separated by only 10 to 100 meters. The space between them became known as “No Man’s Land,” a term that suggested emptiness, a void belonging to neither side.

But something unexpected happened in that supposedly empty space. The very closeness of the enemy lines created the possibility for mutual observation and, more significantly, for a space that was, in practice, collectively shared by both sides.

It was the creation of this shared space that set in motion a series of actions and behaviors that would progressively lead toward the massive Christmas ceasefire.

When Idealism Fades: The Emergence of Accommodation

By December 1914, most of the men fighting were veterans who had witnessed months of mechanized slaughter. Whatever idealism they had carried into battle about the nobility of the cause had largely evaporated in the face of the grinding, dehumanizing reality of trench warfare.

As enthusiasm for combat waned on both sides, something subtle but significant began to happen. The soldiers started creating practices to accommodate their basic human needs and bring small measures of civility to the barbaric conditions they endured together.

Letters and military records document numerous examples of these “accommodating practices.” At various points along the front, soldiers on opposing sides established temporary, unspoken ceasefires when a man needed to relieve himself—a basic human necessity that transcended national allegiance.

Increasingly, rival soldiers would shout across No Man’s Land to communicate about specific events. A correspondent from the Daily Express reported an incident in which German soldiers sent their British opponents an invitation to a birthday concert, noting they would cease firing during the performance. The invitation arrived with a chocolate cake. At another location, soldiers used a dog as a courier between rival trenches, exchanging newspapers, postcards, and even cognac.

These actions represented what we might call “micro-risks”—small experiments with dual identities. The soldiers remained enemies in the official narrative of the war, yet they were simultaneously human beings who recognized in each other a shared need for dignity and normalcy.

In effect, they were creating liminal states—psychological spaces where war and peace coexisted, initiated not by command but by their own choices and behaviors. To varying degrees, they were engaged in a process of transitioning across the boundaries their governments had drawn.

“Something in Common”: When Shared Humanity Surfaces

Both governments recognized that morale among frontline troops was dangerously low. As Christmas approached, each side made efforts to lift spirits. Emperor William II sent miniature Christmas trees adorned with candles to German soldiers. King George V delivered over two million Christmas cards to British troops, and Princess Mary distributed Christmas boxes containing cigarettes, tobacco, chocolate, and plum puddings.

Slowly, amid the bleakness of the trenches, a Christmas atmosphere began to take shape. Small trees appeared on parapets, their candles flickering in the winter darkness, visible across No Man’s Land to soldiers on both sides.

Then, as Christmas drew near, the weather shifted. The constant, soaking rain that had turned the trenches into rivers of mud gave way to a hard freeze. Ice and snow dusted the landscape along the front, and many soldiers on both sides felt that something spiritual was unfolding.

Bruce Bairnsfather, a soldier who was present, wrote in 1916:

“There was a kind of invisible, intangible feeling extending across the frozen swamp between the two lines, which said, ‘This is Christmas Eve for both of us—something in common.’”

This sense of “something in common” emerged from a shared cultural and spiritual heritage that transcended individual national identities. It awakened in the men a recognition that there was, in fact, more that united them than divided them.

A Pattern Emerges: From Carols to Conversation

While the truce manifested differently in different sectors of the front, a common pattern emerged. One group of soldiers would begin singing Christmas carols—most often the Germans. The opposing side would respond with their own carols, which prompted applause and shouts for an encore. Sometimes a sign would be lifted displaying the greeting “Merry Christmas” or the proposition “You no fight, we no fight.”

Ernest Morley, a Rifleman in the 16th Battalion, London Regiment, described this pattern in a letter home:

“We had decided to give the Germans a Christmas present of three carols and five rounds rapid. Accordingly, as soon as night fell, we started, and the strains of ‘While Shepherds Watched’ (beautifully rendered by the choir!) came upon the air. We finished that and paused preparatory to giving the second item on the programme. But lo! We heard answering strains arising from their lines. Also, they started shouting across to us. Therefore, we stopped any hostile operations and commenced to shout back. One of them shouted ‘A Merry Christmas English, we’re not shooting tonight.’ We yelled back a similar message.”

Shared Hardships: Building Connection Through Common Ground

With the space between trenches now frozen solid, movement became easier. Once soldiers ventured into No Man’s Land, they began sharing stories about the common hardships of trench life and discussing possible solutions.

How could they keep their gear dry?

How could they manage the infestations of lice and rats?

These concerns were universal, regardless of which side a man fought for, and discussing them required no betrayal of military secrets. The appalling conditions they all endured became a foundation for emotional connection and solidarity that existed entirely apart from their national allegiances.

Burying the Dead Together: Connection at the Existential Level

Once in No Man’s Land, soldiers on both sides confronted the overwhelming smell of decomposing bodies—a visceral reminder not only of the magnitude of their shared situation but also of the fate that likely awaited them all.

Each side began to bury their own dead. But as rival soldiers intermingled in that space, something remarkable happened: joint burials began to occur.

Arthur Pelham-Burn, a Second Lieutenant in the 6th Battalion Gordon Highlanders, was stationed west of Lille, France, where the trenches were separated by only 60 yards. In a letter home, he described a mass burial in which German and British soldiers together interred more than 100 bodies:

“A service of prayer was arranged and amongst them was a reading of the 23rd Psalm and an interpreter wrote them out in German. They were read first in English by our Padre and then in German by a boy who was studying for the ministry. It was an extraordinary and wonderful sight. The Germans formed up on one side, the English on the other, the officers standing in front, every head bared. Yes, I think it was a sight one will never see again.”

Life-Affirming Exchanges: Beer, Haircuts, and Shared Cigarettes

Yet even amid the solemnity of burying the dead, the soldiers found ways to connect that affirmed life. Germans were often happy to trade their plentiful supply of beer for British plum and apple jam. Mutual hair trimmings were reported, as were scavenger hunts for corned beef and uniform buttons. On more than a few occasions, rival soldiers were seen sharing a smoke.

The actions in No Man’s Land evolved progressively—from individual gestures to interactions between pairs of rival soldiers to, finally, more coordinated collective efforts between larger groups of troops.

The Football Matches: Spontaneous Games in the Space Between

The widely reported football games that emerged can be understood as the culmination of these accumulating efforts. They occurred at various locations in No Man’s Land, ranging from informal kickabouts to something approximating organized matches with chosen teams and recorded scores. When no soccer ball was available, the men improvised with caps, tin cans, and whatever else they could find.

What stands out is that all of these games were spontaneous, instigated entirely by the soldiers themselves. Private Ernie Williams of the Cheshire Regiment reinforced this point:

“A ball appeared from somewhere, I don’t know where, but it came from their side. They made up some goals and one fellow went in the goal and then it was just a general kickabout. I should think there were a couple hundred taking part. I had a go at the ball. Everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. There was no sort of ill-will between us. There was no referee and no score, no tally at all.”

More Than Magic—An Accumulation of Ordinary Choices

In 2022, historians A.J. Baime and Volker Janssen described the Christmas Truce as “one of the most storied and strangest moments of the Great War—or of any war in history.”

One hundred thousand men, commissioned to kill one another, created instead a space of civility, recognition, and shared celebration. It is tempting to see the episode as pure magic: a fleeting suspension of reality, an historical anomaly that resists explanation.

Yet, what appears, from a distance, as a miracle often looks very different when examined from within the ordinary, cumulative choices that made it possible. Here, in this examination is where the challenge lies for us if we are to lay bear the mystery of this event and make it, even in some small way, repeatable in our times.

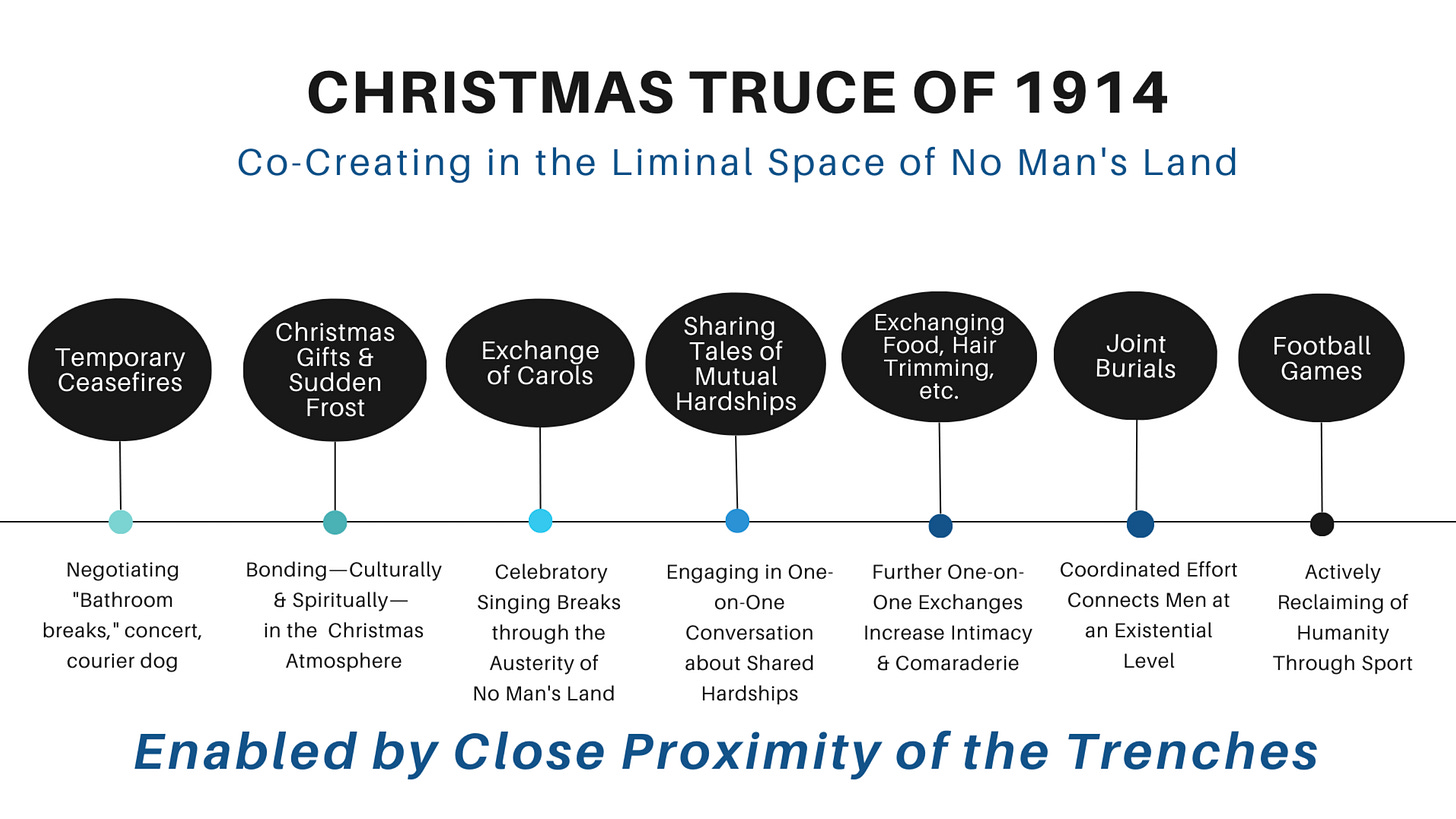

The diagram below traces the behaviors, actions, and conditions that appear to have laid the groundwork for the ceasefire that emerged.

The close proximity of the trenches which also created a shared space between the opposing soldiers was a critical component. It created the possibility for mutual recognition—for soldiers to see that the fears, discomforts, and needs of those across the lines mirrored their own. Within this environment, individuals began to test the boundaries of what might be possible through small, tentative acts: calling out, agreeing not to fire at certain moments, exchanging objects, acknowledging shared hardships.

Each gesture carried risk. None altered the official status of the war. Yet each subtly expanded the psychological space in which soldiers could hold dual identities at once: enemy combatant and fellow human being.

Over time, these individual acts accumulated. Interactions that began between pairs of soldiers widened into collective practices—joint burials, shared songs, spontaneous games—until the logic of war itself was temporarily suspended. No orders were given. No agreements were signed. The transformation emerged from below, through action rather than intention.

Fraternization with the enemy has always stood in direct violation of military doctrine. Yet for the men in the trenches, the inhuman conditions of daily life and the constant presence of death carried more weight than rules imposed from a distant command. In that context, restraint became not an abstraction but a lived necessity.

Through this incremental process, tens of thousands of soldiers set aside their assigned roles long enough to co-create a space governed by recognition rather than violence—a space that existed only because they continued to act as if it could.

What We Can Learn: The Power of Concrete Action

Reflecting on the Christmas Truce, Substack CEO Chris Best has written,

“The drive to war is very human, but peace can also stir our hearts.”

The Truce suggests something more precise—and more demanding—than a stirring of sentiment. It shows that peace can take shape through concrete behaviors, specific choices, and calculated micro-risks, even under conditions designed to make such choices unthinkable.

The soldiers of 1914 did not wait for permission. They did not wait for guarantees. They did not wait for the other side to move first. They acted—tentatively, imperfectly, and at significant personal risk—to create conditions in which something other than violence could emerge.

They transformed No Man’s Land from a killing field into shared ground through accumulated acts of recognition and reciprocity. In doing so, they revealed a form of agency that does not depend on authority or agreement, but on the willingness to behave differently in the presence of an enemy.

As we confront our own divisions—political, social, and ideological—that feel increasingly fixed and impermeable, the Christmas Truce offers neither blueprint nor reassurance. It offers something quieter and more unsettling: evidence that even in the most constraining circumstances, human beings retain the capacity to interrupt the logic that governs them.

The soldiers of 1914 did not end the war. The machinery of violence soon reasserted itself. Yet for a brief and fragile interval, they demonstrated that peace does not always arrive through understanding, negotiation, or command. Sometimes it emerges when people choose, against expectation and instruction, to recognize one another as human first.

Sources

Dash, M. (2011, December 3). The Story of the WWI Christmas Truce. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-story-of-the-wwi-christmas-truce-11972213/

The Gazette (n.d.). World War I: The Christmas Truce of December 1914. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/awards-andaccreditation/content/287

The National World War I Museum and Memorial. “Trench Warfare: Life in the Trenches: 1914-1919.” https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/trench-warfare

Weintraub, S. (2001). Silent Night: The Story of World War I Christmas Truce. New York: Free Press.

Woodward, D. R. (2011). Christmas Truce of 1914: Empathy Under Fire. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 91(1), 18-19.