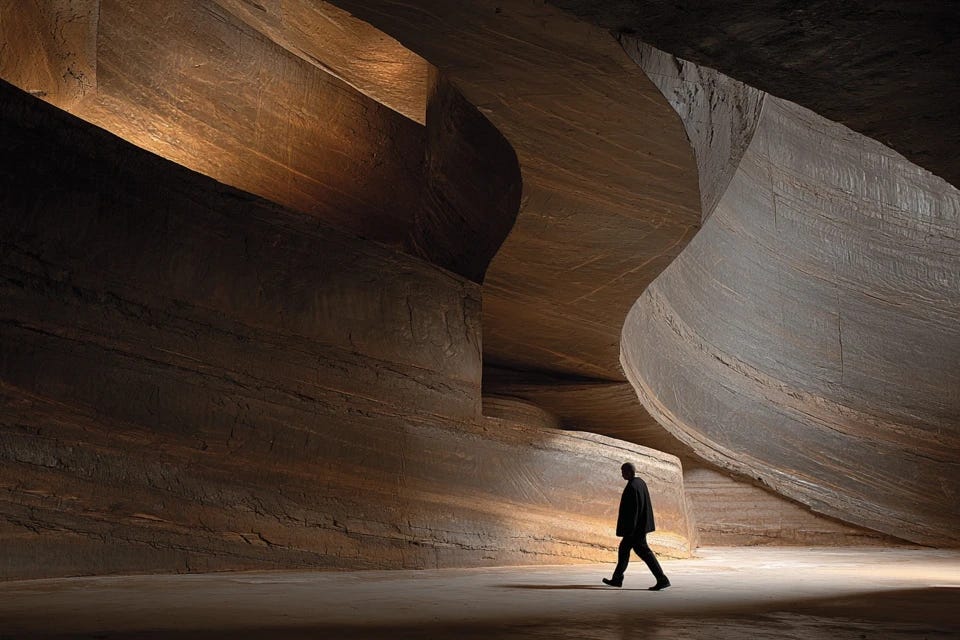

Entering the Non-Negotiable

Carsten Stolz on how death awareness shapes executive leadership in midlife

As business leaders grapple with unprecedented global uncertainties, a deeper psychological reckoning may be reshaping how they lead.

The corporate world has never felt more volatile. From AI disruption to climate change, from geopolitical tensions to demographic shifts, today’s executives navigate crises that would have been unimaginable a generation ago. But beneath these visible challenges lies a more personal reckoning that rarely makes it into boardroom discussions: the growing awareness of mortality among leaders entering their 50s and 60s.

As the workforce ages and careers extend well beyond traditional retirement, a new phenomenon is emerging. Senior executives who once felt invincible are confronting what researcher Carsten Stolz calls “entering the non-negotiable”—the undeniable reality of death. This confrontation, Stolz’s research suggests, is fundamentally reshaping how leaders think, decide, and act in their professional roles.

The Invisible Weight of Mortality

In a comprehensive study of 13 senior executives at midlife, Stolz uncovered a paradox at the heart of modern leadership. Just as these professionals reach their career peaks—wielding unprecedented influence and responsibility—they’re simultaneously grappling with an intensely personal adaptive challenge: accepting their own mortality.

“Around midlife, executives are ‘entering the non-negotiable’: death becomes more apparent,” Stolz writes in his study.

“For experienced executives leading organizations through major change, becoming aware of death forces them to engage in two simultaneous adaptive challenges, one highly personal, the other more fully professional.”

This dual challenge is particularly acute in today’s business environment. As companies demand longer working lives and the boundary between active and retired life blurs, executives find themselves confronting existential questions while simultaneously expected to guide organizations through transformation. The timing couldn’t be more critical—or more complex.

Three Faces of Death Awareness

Stolz’s research identifies three distinct dimensions of death awareness that shape executive psychology:

Physical Death Awareness emerges from direct encounters with mortality—the death of loved ones, personal health scares, or simply the accumulating physical wear of demanding careers. One executive in Stolz’s study recalled how a terminal illness diagnosis brought everything “to a grinding halt,” shattering the assumption that he could “work for eternity.”

Consciousness Death Awareness involves grappling with philosophical questions about what happens after death. Surprisingly, Stolz found that many executives—often stereotyped as purely rational—harbor deep spiritual beliefs about consciousness continuing beyond physical death.

Metaphoric Death Awareness encompasses the “deaths” that occur throughout life: career transitions, divorce, loss of identity, or disconnection from one’s authentic self. This dimension proved particularly relevant for midlife leaders questioning whether they’ve been living authentically or merely fulfilling others’ expectations.

The Perfectionism Trap

One of Stolz’s most striking insights concerns the relationship between perfectionism and death anxiety. Many high-achieving executives have built their careers on perfectionist tendencies—a trait that can serve them well in solving technical problems but becomes problematic when facing existential challenges.

“Perfectionism is a personality characteristic of a person who is striving to be flawless, sets high performance standards for himself while being self-critical and concerned about others’ evaluations,” Stolz explains. While adaptive perfectionism can drive achievement, it can become maladaptive when executives try to apply the same controlling mindset to mortality—the ultimate uncontrollable reality.

This perfectionist trap is compounded by what psychologists call “contingent self-esteem”—self-worth that depends on external validation. Executives who’ve climbed corporate ladders often rely heavily on professional success and social approval for their sense of value. When confronted with mortality, these external sources of validation suddenly feel inadequate.

The Organizational Impact

The implications extend far beyond individual psychology. Stolz’s research suggests that executives’ unconscious responses to mortality awareness can significantly impact organizational behavior—sometimes in counterproductive ways.

Leaders struggling with death anxiety might become overly controlling, resist necessary changes, or make decisions driven more by legacy concerns than business logic. Alternatively, they might engage in what Stolz terms “anti-task” behavior—actions that actually work against organizational goals while serving psychological needs for immortality or meaning.

“Unawareness about how the death threat influences one’s own cognition, emotion, and behaviour can result in un-reflected, maladaptive responses and lead to ‘off-task’ or even ‘anti-task’ acts,” Stolz warns. “This is particularly important for senior executives since they are connected to the social system of their organization through their powerful role.”

Consider the current business environment: companies desperately need adaptive, innovative leadership to navigate AI transformation, sustainability challenges, and changing workforce expectations. But if senior leaders are unconsciously driven by mortality anxiety, they may default to familiar strategies that provide psychological comfort rather than organizational effectiveness.

The Quest for Immortality

When able to more fully embrace a more balanced sense of death awareness, the executives in Stolz’s study exhibited six common responses—what he terms their “quest for immortality”:

Being in the Here and Now: A heightened focus on present-moment awareness and authenticity

Focus and Commitment: Intensified dedication to meaningful work and relationships

Leaving a Good Legacy: Increased concern with how they’ll be remembered

Selectivity: More careful choices about how to spend time and energy

Caring for Resources: Better attention to physical and emotional well-being

Authoring One’s Self: A drive toward authenticity and individuation, independent of external expectations

These responses can be profoundly positive for both leaders and organizations—if they’re conscious and well-managed. Leaders who successfully navigate their mortality awareness often become more authentic, focused, and generative. They’re less likely to chase empty status symbols and more likely to invest in developing others and creating lasting value.

The Tightrope Walk

But there’s a delicate balance to strike. Stolz describes the midlife executive’s challenge as a “tightrope walk between safeguarding what he has achieved and pursuing individuation.” On one side lies the safe path of maintaining existing success; on the other lies the riskier journey toward authentic self-expression and meaning.

This tension is particularly acute in today’s hyper-connected, always-on business culture. Organizations often demand total commitment from senior leaders, creating what Stolz calls “hyper-inclusive social systems” that absorb executives so completely that they become disconnected from other important relationships and aspects of themselves.

“The more inclusion the system requests and the higher the executive’s need for validating contingent parts of his self-esteem, the stronger the risk that the executive’s capacity to provide direction, protection, order, and meaning is impaired,” Stolz observes.

A New Leadership Paradigm

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated many of these dynamics, forcing leaders to confront mortality on both personal and organizational levels. The executives who thrived weren’t necessarily those with the strongest technical skills, but those who could sit with uncertainty, make meaning from chaos, and maintain authentic connections with their teams.

This points toward a new leadership paradigm—one that acknowledges the full humanity of leaders, including their mortality. Rather than demanding superhuman invulnerability, organizations might benefit from leaders who’ve done the inner work of confronting their own mortality and emerged more integrated, authentic, and purposeful.

Stolz’s research suggests several practical implications:

For Individual Leaders: Regular self-reflection about mortality and meaning isn’t morbid—it’s essential. Leaders who understand their own death anxiety buffers are less likely to make decisions driven by unconscious fears and more likely to act from wisdom and authenticity.

For Organizations: Creating space for leaders to process existential questions isn’t soft—it’s strategic. Companies that support their executives’ developmental journeys are likely to see more innovative, adaptive, and sustainable leadership.

For Leadership Development: Traditional executive education focuses heavily on technical and strategic skills while ignoring the psychological and existential dimensions of leadership. A more holistic approach would help leaders navigate the full complexity of their roles.

The Light Through the Cracks

Perhaps this is the deepest insight from Stolz’s research: that acknowledging our mortality and imperfection doesn’t make us weaker leaders—it makes us more complete ones. The vulnerability that comes with confronting death isn’t a liability to be hidden but a source of wisdom to be integrated into how we lead.

In a world facing unprecedented challenges that require unprecedented wisdom, we may need leaders who have moved beyond the illusion of invulnerability. The executives who will thrive in the coming decades may not be those who deny death’s reality, but those who have learned to live fully in its presence—using their awareness of life’s preciousness and limits to guide them toward more authentic, purposeful, and effective leadership.

This shift represents more than personal development; it’s a fundamental reimagining of what strong leadership looks like.

When leaders can sit with their own mortality without being consumed by anxiety, they become capable of making decisions from a deeper place—one less driven by ego protection and legacy concern, and more aligned with genuine value creation and human flourishing.

For midlife executives willing to face their own mortality with courage and consciousness, the confrontation becomes not an ending but a beginning—a portal to a more integrated way of leading that serves both their organizations and their own journey toward meaning. In embracing what cannot be negotiated, they may discover what truly matters most.

Carsten Stolz currently serves as Group Chief Finance Officer at the Baloise Group, where he has worked in the C-Suite for 15 years. He earned his doctorate in financial management from Fribourg University and an Executive Master in Change from INSEAD, where he was awarded Distinction.

This article draws from Stolz’s 2018 Executive Master in Change thesis “Entering the Non-Negotiable: Death Awareness and its Transcendence into Midlife Adaptive Challenges.” While the research offers valuable insights, readers should note that it was based on a small sample of 13 executives and represents one perspective on complex psychological phenomena. Leaders struggling with existential concerns may benefit from working with qualified coaches, therapists, or spiritual advisors.

References

Becker, E. (1974). The Denial of Death. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss - Volume 1 - Attachment. London: Pimlico.

Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly: how the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. New York: Penguin Random House.

Cohen, L. (1992). “Anthem.” The Future. Columbia Records.

Erikson, E. H. (2017). Identität und Lebenszyklus (28th ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Frankl, V. (1985). Men’s Search for Meaning. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Greenberg, J., Pyszcynski, T., Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189–207). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hollis, J. (1993). The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife. Toronto: Inner City Books.

Johnson, M., & Blom, V. (2007). Development and validation of two measures of contingent self-esteem. Individual Differences Research, 5(4), 300–328.

Jung, C. G. (1921). Psychologische Typen. Zürich, Leipzig and Stuttgart: Rascher & Cie.

Kegan, R. (1982). The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kets de Vries, M. (2014). Death and the executive: Encounters with the “Stealth” motivator. Organizational Dynamics, 43(4), 247–256.

Kübler-Ross, E. (2014). On Death & Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy & Their Own Families. New York: Scribner.

Miller, A. (2007). Death of a Salesman. Stuttgart: Reclam.

Pinkola Estés, C. (1995). Women Who Run With the Wolves. New York: Ballentine Books.

Stoeber, J., & Childs, J. H. (2010). The assessment of self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism: Subscales make a difference. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(6), 577–585.

Stolz, C. (2018). Entering the “Non-Negotiable”: Death Awareness and its Transcendence into Midlife Adaptive Challenges. EMCCC Thesis.

Yalom, I. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.