How did 100,000 soldiers put a war on hold?

As the war in Gaza rages, a reflection on the psychodynamics of the impossible

It has long been seen as a nearly unfathomable event—the Christmas Truce of 1914.

And on this the first day of 2024, as our world stands witness to a war in Gaza that has left 22,000 dead and 56,000 wounded, it is an event worth revisiting.

The undisputed facts are these:

From December 24-26 in 1914, five months into World War I, a war that had already taken over one million lives and that would go on to claim 25 million more, an unofficial and impromptu cease-first occurred along the Western Front.

While not sanctioned by the commanders on either side, along some two-thirds of the front controlled by the British Expeditionary Force, guns fell silent.

And men charged with killing one another—close to 100,000 in number—emerged from their trenches to sing Christmas carols, share food, engage in conversation, and come together for an unlikely game of football.

What occurred on those three days over 100 years ago seems nothing short of a miracle. Other worldly. Possibly more myth than reality. Certainly, something that surpasses our conventional understanding.

Yet, a reversal of this magnitude among such a large number of people marked as enemies cannot be a matter of coincidence. What then was behind it?

In the simplest of terms, the question before us is this:

How was it possible for 100,000 British and German soldiers to put a war on hold without the approval of their superiors?

Now that is a question worth unraveling.

To that end, let us first look back over the weeks and months prior to the event.

Entering “No Man’s Land” — A Mutually Constructed Social Order

In the early months of WWI, the war machine was running at full speed, leaving one million dead by late November. In an effort to protect the soldiers from the relentless gun and artillery fired, trenches were built starting along the 475-mile-long Western Front.

These rival trenches were placed in close proximity to one another, often only 10-100 meters apart, and the space between them was known as “No Man’s Land”.

Having these enemies separated often by a mere 10-20 meters opened up the possibility for mutual observation and the creation of a space “collectively shared”.

It was the creation of this shared space that set the stage for a series of actions and behaviors that progressively lead toward this massive ceasefire of over 100,000 men.

As Enthusiasm Waned, Accommodating Practices Emerged

By December of 1914, the majority of those fighting were veterans of the conflict who were now largely void of any idealism regarding the great purposes of the war.

As the aggression on both sides decreased, these soldiers started to put in place practices to accommodate their human needs and bring some civility to the barbaric conditions of trench warfare.

Temporary ceasefires for “bathroom breaks”, a birthday concert & a courier dog

Letters and records document numerous examples of these “accommodating practices”. One that occurred at various locations across the front was the creation of a temporary ceasefire agreed upon by the soldiers when a soldier needed to relieve himself.

Increasingly the rival soldiers would shout across to each other, communicating about specific events. A correspondent from the Daily Express reported of an incident in which Germans sent the opposing troops an invitation to a birthday concert, noting that they planned to cease firing during that time—the invitation came with a chocolate cake. At another location, a dog was used to communicate back and forth between rival trenches, exchanging newspapers, postcards and even cognac.

The impact of the trenches’ close proximity and the shared space between, set within the waning enthusiasm of the soldiers, prompted the men to take what could be called “micro-risks” and experiment with dual identities. On one hand, they were enemies to each other; on the other, they were human beings with a shared need for dignity.

These actions meant that they were starting to exist, periodically, within liminal states of war and peace, initiated by their own behaviors and decisions. In short, to varying degrees, they were entering into a psychological process of transitioning across boundaries.

‘Something in Common’ — There is more that unites us than divides us

That morale was low among the troops across the font was no secret to their governments. As Christmas approached, each made efforts to bolster their spirits. Emperor William II sent tabletop Christmas trees adorned with candles; King George V delivered over two million Christmas cards to the British soldiers and Princess Mary gave Christmas boxes that included cigarettes and tobacco, along with chocolate and plum puddings.

Slowly, among the bleakness of the trenches, a Christmas atmosphere began to emerge, and small trees — their tiny candles lit — were seen across No Man’s Land.

Then, suddenly, as Christmas drew near, the constant soaking rain gave way to a hard front, creating a dusting of ice and snow along the front that made the men on both sides feel that something spiritual was unfolding.

One soldier present, Bruce Bairnsfather, wrote in 1916:

“There was a kind of invisible, intangible feeling extending across the frozen swamp between the two lines, which said, ‘This is Christmas Eve for both of us — something in common.’”

This “something in common” grew out of a shared cultural and spiritual background that transcended the men’s individual identities and stirred within them a sense that there was, in fact, more that united them than divided them.

A Pattern of Connection Emerges — Beginning with a Song

While the truce unfolded differently in different areas of the front, a common pattern was evident. One group of soldiers would start singing Christmas carols—most often the Germans. The opposing side would then respond with their own carols, which brought on applauds and shouts for an encore. Sometimes a paper was lifted, displaying the greeting ‘Merry Christmas’ or the suggestion, ‘You no fight, we no fight’.

Ernest Morley, a Rifleman in the 16th Battalion, London Regiment, described this very pattern in a letter home to a friend:

We had decided to give the Germans a Christmas present of three carols and five rounds rapid. Accordingly, as soon as night fell, we started, and the strains of ‘While shepherd’ (beautifully rendered by the choir!) came upon the air. We finished that and paused preparatory to giving the second item on the programme. But lo! We heard answering strains arising from their lines. Also, they started shouting across to us. Therefore, we stopped any hostile operations and commenced to shout back. One of them shouted ‘A Merry Christmas English, we’re not shooting tonight’. We yelled back a similar message.

Conversation & Tales of Common Hardships

With the space between the trenches now covered with a hard frost, the men were able to move more easily, and, once between the lines, they began to share trench tales of common hardships and possible solutions with the opposing troops.

How could they keep things dry?

How could they handle the lice and rats?

These concerns were ones easily related to by all, regardless of affiliation, and had nothing to do with sensitive military information. The appalling state of their shared living conditions served as a platform for an emotional connection and solidarity that did not require them to betray their respective nations.

Joint Burials Knit the Men Together at an Existential Level

Now in No Man’s Land, the soldiers were met with the smell of decaying corpses—a stench that reminded them not only of the magnitude of their shared situation, but also of what fate likely awaited them. Each side began to bury their own, but soon, as rival soldiers intermingled, joint burials started to occur.

Arthur Pelham-Burn, a Second Lieutenant in the 6th Battalion Gordon Highlanders, was stationed west of Lille, France, where the trenches were only 60 yards apart. In a letter home to a friend, he describes a mass burial that occurred when the Germans and British buried the more than 100 bodies:

“… awful, too awful to describe, so I won’t attempt it. A service of prayer was arranged and amongst them was a reading of the 23rd Psalm an an interpreter wrote them out in German. They were read first in English by our Padre and then in German by a boy who was studying for the ministry. It was an extraordinary and wonderful sight. The Germans formed up on one side, the English on the other, the officers standing in front, every head bared. Yes, I think it was a sight one will never see again.”

Exchanging food, mutual hair trimmings & scavenger hunts

Yet, even amid this most sober of settings, the soldiers found ways to connect that were life affirming. The Germans were often glad to exchange their ample supply of beer for the English plum and apple jam, and the British were happy to oblige. Mutual hair trimming were reported, as well as scavenger hunts for corned beef and buttons. And on more than a few occasions, rival soldiers were seen sharing a smoke.

These actions in No Man’s Land moved progressively from individual gestures to actions between two rival soldiers to, finally, more coordinated joint efforts between the troops.

A Ball Appeared Out of Nowhere — Spontaneous Football Matches

The much-reported football games that came next can easily be seen as representing a culmination of these cumulating efforts. They occurred at various spots in No Man’s Land, ranging from unorganized kickabouts to something closer to a real match with teams chosen and scores recorded. Even when a soccer ball was not available, the men found ways to do without, substituting caps, tin cans and whatever else could come up with for a ball.

But what is noteworthy is that all of these games were spontaneous endeavors instigated by the men. Private Ernie Williams of the Cheshire Regime comments reinforce this:

“A ball appeared from somewhere, I don’t know where, but it came from their side…. They made up some goals and one fellow went in the goal and then it was just a general kickabout. I should think there were a couple hundred taking part. I had a go at the ball. Everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. There was no sort of ill-will between us. There was no referee and no score, no tally at all.”

More than a Mystery

In 2022, A.J. Baime and Volker Janssen wrote of the Christmas Truce of 1914:

… it remains one of the most storied and strangest moments of the Great War— or of any war in history.

One hundred thousand men, commissioned to kill, came together instead to create a space of civility and celebration. How could it be other than a magical moment, something of happenstance, a “one-off” occurrence with no logical reason for its being?

Yet, if we refrain from retreating into romanticism and instead confront the reality that 100,000 people were somehow able to pull this off, then we may well be able to learn something valuable for our own time.

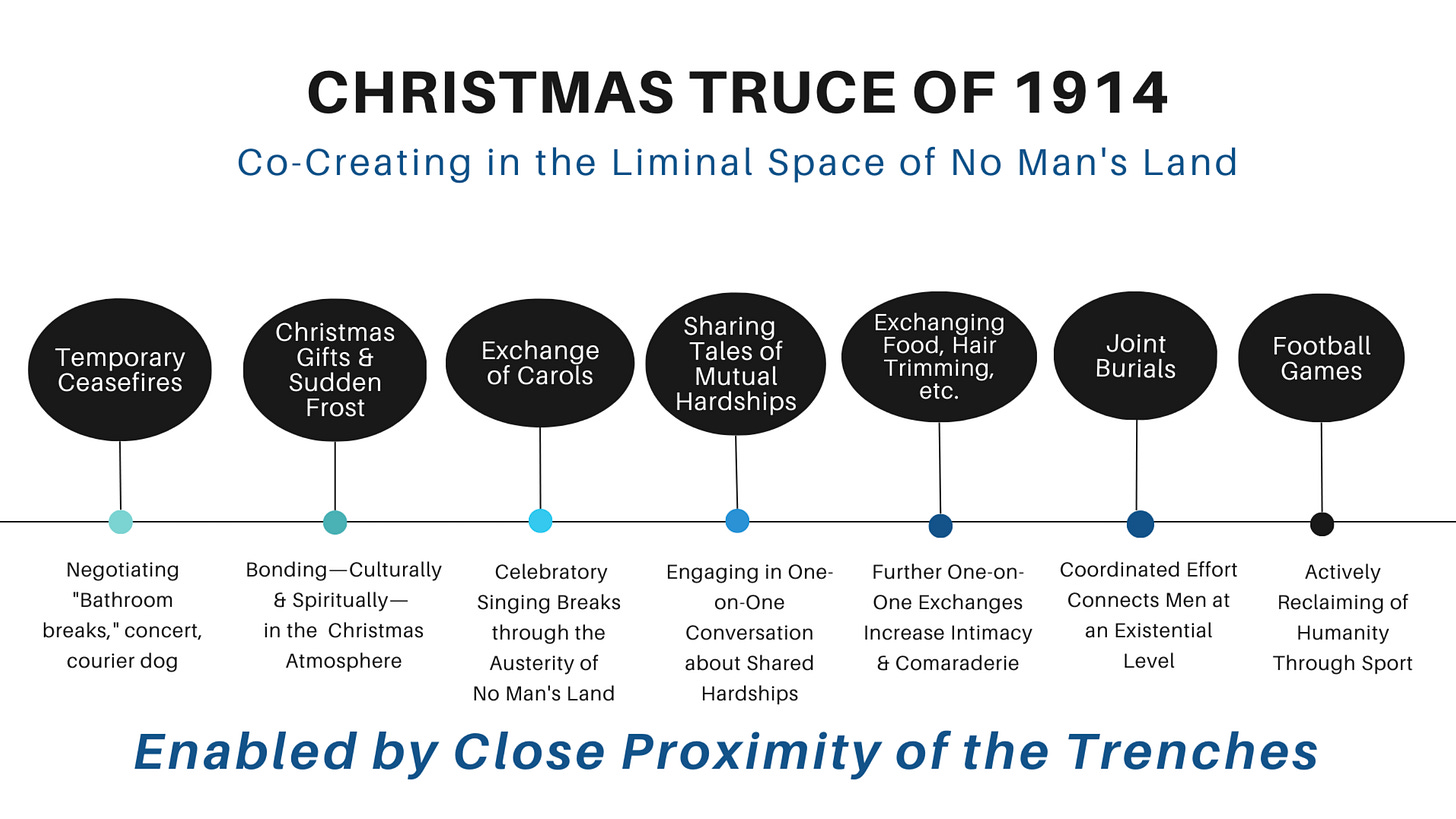

As a first step in that direction, the diagram below gives an overview of key behaviors, actions and environmental conditions that preceded the truce and that appear to have laid the groundwork for its coming into being.

The close proximity of the trenches was a fundamental factor. It created the possibility for the soldiers to notice that their own concerns were shared by their enemies. As the diagram suggests, individuals began to take action, testing the waters of what might be possible. All of this occurred in tentative steps, with each one preparing the ground for the next. Increasingly the opposing armies intermingled and their actions became collective and eventually coordinated, culminating in the joint burials and final football games.

Fraternizing with the enemy has long been fundamentally counter to the code of war. Yet, the soldiers on both sides seemed drawn to test the bounds of that absolute and ultimately violate it openly. The inhumane living conditions of the trenches and the massive causalities on both sides—clearly evidence before their eyes by the corpses scattered in No Man’s Land—appears to have held greater sway in their minds and hearts, than the rules of war.

In the end, through this incremental process, those men, 100,000 in number, suspended their war roles and all the associated rules in order to co-create with their enemies a space of civility and celebration.

*****************

In reflecting on Christmas Truce of 1914, Substack CEO Chris Best writes in The Coming Culture Peace:

If there is a lesson to be learned from the Truce of 1914, it is not only that peace stirs in the human heart, but also that through concrete actions, behaviors, and micro-risks executed sometimes in the most threatening of situations, even a peace like this one, which seems to surpass the limits of our understanding, can, in fact, unfold.

Sources:

Dash, M. (2011, December 3). The Story of the WWI Christmas Truce. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-story-of-the-wwi-christmas-truce-11972213/

The Gazette (n.d.). World War I: The Christmas Truce of December 1914. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/awards-andaccreditation/content/287

The National World War I Museum and Memorial. “Trench Warfare: Life in the Trenches: 1914-1919. https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/trench-warfare

Weintraub, S. (2001). Silent Night: The Story of World War I Christmas Truce. New York: Free Press.

Woodward, D. R. (2011). Christmas Truce of 1914: Empathy Under Fire. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 91(1), 18-19.