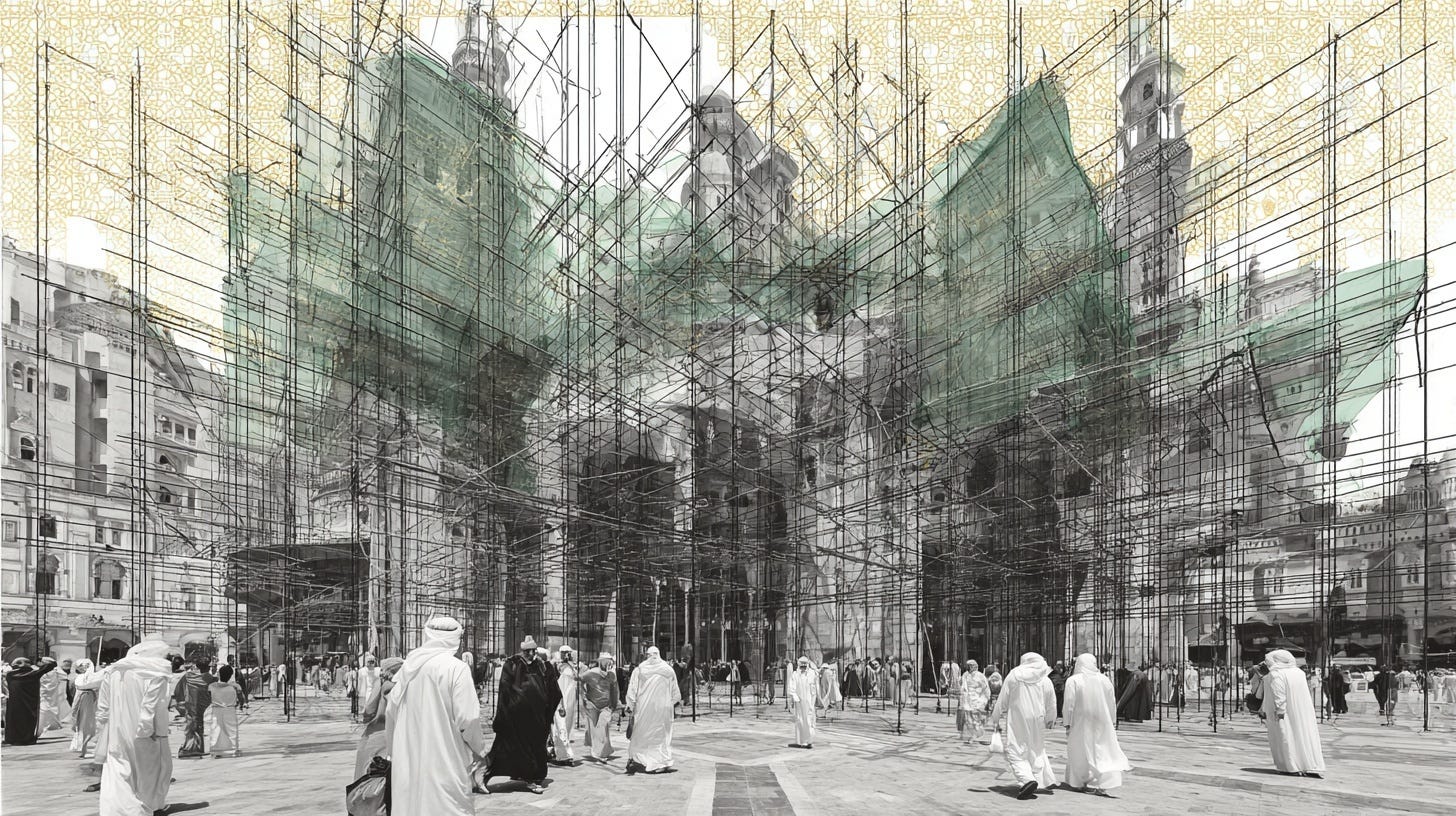

The Invisible Architecture

Ahmed El-Orabi on how family dynamics shape organizations & leadership in the Middle East

In an era of rapid organizational transformation and calls for workplace reform across the Arab world, the most powerful barrier to change may be the one we carry within us—unexamined patterns learned at the dinner table.

From Dubai’s gleaming corporate towers to Cairo’s bustling start-up hubs, from Riyadh’s Vision 2030 initiatives to Beirut’s creative agencies, Middle Eastern organizations are racing to modernize. Governments are launching ambitious reform programs. International consultants are redesigning hierarchies. And leadership development programs proliferate.

Yet beneath the surface of these institutional changes, a more fundamental force continues to shape how power actually operates in these spaces: the family.

As the region grapples with record youth unemployment, brain drain, and the challenge of building knowledge economies that can compete globally, understanding this invisible architecture has never been more urgent.

• Why do so many talented young professionals leave the region?

• Why do innovation initiatives often fail to take root?

• Why does workplace culture so frequently feel stifling, despite stated commitments to empowerment and creativity?

According to Ahmed El-Orabi, consultant, researcher and alumnus of INSEAD’s prestigious Executive Master in Change programme, the answers may lie not in organizational charts or mission statements, but in the dining rooms and living rooms where we first learned what authority means.

The Family as Society’s Foundation

El-Orabi’s research reminds us that, in Middle Eastern societies, the family occupies a position of centrality that distinguishes the region from much of the industrialized West. This is not merely a cultural preference but a structural reality that shapes every aspect of social organization. Extended family networks remain the primary source of economic support, social identity, and emotional belonging. Marriage continues to be understood less as the union of two individuals than as the alliance of two families. Inheritance laws, property ownership, and business partnerships all reflect the assumption that the family, not the individual, is the fundamental unit of society.

This centrality, as El-Orabi points out, means that the family serves as the original classroom for learning about power, hierarchy, and relationship. Long before a child encounters formal institutions—schools, governments, corporations—they have already internalized complex lessons about authority from their position within the household. Who speaks and who listens? Who commands and who obeys? Whose dreams matter and whose must be deferred? These early experiences create internal templates that persist, often unconsciously, throughout life.

The household becomes a miniature political system, complete with its own hierarchies, alliances, and unspoken rules. The father, traditionally, occupies the apex of this system—provider, protector, and ultimate arbiter of major decisions. His authority is rarely questioned openly, even when it may be resisted privately. The mother, while often wielding considerable influence within domestic spheres, typically operates through indirect channels of power. Children learn to navigate this landscape through a complex calculus of obedience, strategic compliance, and the careful management of parental expectations.

The Choreography of Love and Control

What makes this dynamic particularly psychologically complex, according to El-Orabi, is that authority in Middle Eastern families is rarely experienced as purely coercive. It is wrapped in the language of love, sacrifice, and devotion. Parents genuinely believe they are acting in their children’s best interests when they chart educational paths, influence career choices, or arrange marriages. The narrative of parental sacrifice is powerful and pervasive: parents have given everything—their youth, their resources, their very lives—so that their children might prosper. How can children, then, refuse what is asked of them?

This creates a distinctive emotional register where care and control become intertwined in ways that can be difficult to disentangle. A father who insists his son become a physician may be motivated by genuine concern for the son’s financial security and social standing. Yet this concern, however authentic, can also function as a form of domination—a commandeering of the son’s life narrative to fulfill the father’s own unmet ambitions or to maintain the family’s status.

Consider a common scenario: a young man dreams of becoming an artist or a writer, but his father, a successful businessman, insists he study engineering or medicine. The father’s reasoning seems sound: creative fields offer uncertain futures, while professions provide stability and respect. He frames his insistence as wisdom born of experience, as protection against hardship he himself has known. The son, taught from earliest childhood to honor his father’s judgment, feels the weight of this expectation as something more than preference—it carries the moral force of duty, loyalty, and gratitude.

Yet beneath this ostensibly rational calculus lies something more psychologically fraught. The father’s insistence may also express his own unlived life—his own abandoned dreams of distinction, his need to prove to his own father (now deceased) that his line has produced someone of stature. The son becomes not just himself, but a vessel for multiple generations of hope, disappointment, and aspiration. To pursue his own dream is not merely a personal choice; it becomes an act of betrayal, a rejection of everything the family has sacrificed.

The Translation into Organizational Life

According to El-Orabi, these patterns do not remain confined to the family home. They migrate, often without conscious awareness, into professional contexts. The young man who learned to silence his own desires to fulfill his father’s expectations may, years later, find himself doing the same to his subordinates. Having internalized the equation of authority with superior knowledge and legitimate control, he reproduces it naturally when he himself rises to positions of leadership.

This is not hypocrisy, but rather the working of unconscious loyalty. We tend to recreate what we know, even when what we know has caused us pain. The manager who was once stifled by paternal authority genuinely believes he is being a strong, decisive leader when he dismisses subordinates’ input, makes unilateral decisions, and expects compliance without question. He has simply activated the template for authority that was etched into his psyche decades earlier.

As El-Orabi points out, the organizational consequences are profound.

In workplaces structured by these unconscious family patterns, hierarchy becomes rigid and communication flows primarily downward. Questioning decisions is interpreted not as healthy critical thinking but as insubordination or disrespect. Innovation requires risk-taking and experimentation, but both are dangerous in an environment where errors may be met with shame and punishment rather than learning. Employees learn to manage upward—to present what leadership wants to hear rather than what they actually think or observe.

The result is what organizational psychologists call a “culture of compliance.” People become adept at reading signals, at anticipating what authority figures want, at avoiding blame. Energy that might be directed toward creative problem-solving or genuine collaboration is instead channeled into navigating political dynamics and protecting one’s position. Trust atrophies. Autonomy is experienced as threat rather than opportunity. The organization becomes, in essence, a larger version of the authoritarian family—a place where care and control remain confused, where loyalty is demanded but genuine engagement withers.

The Generational Divide: A Collision of Expectations

Perhaps nowhere is the tension between inherited family patterns and changing realities more evident than in the generational divide now opening across Middle Eastern workplaces. The region is experiencing what might be called a “psychological globalization”—younger professionals, shaped by education abroad, exposure to global media, and digital connectivity, are arriving in traditional organizational settings with fundamentally different assumptions about authority, autonomy, and the purpose of work itself.

This generational shift is not simply about age but about the collision of different psychological formations. Those who entered the workforce in the 1980s and 1990s—today’s senior leadership—came of age in a context where traditional family structures were largely unquestioned, where economic opportunities were more abundant (particularly in oil-rich economies), and where the social contract seemed clearer: work hard, show loyalty, and advancement would follow. For this generation, reproducing family-style authority in organizations felt natural, even necessary for maintaining order and achieving results.

Today’s younger professionals, by contrast, often describe a profound sense of dislocation. A 28-year-old engineer in Amman, educated at a European university, returns to find that her ideas are dismissed not on their merits but because of her junior status. A Dubai-based analyst with an MBA realizes that promotions depend less on performance than on personal relationships with senior management. A young entrepreneur in Cairo discovers that challenging a bad decision in a meeting is seen not as constructive feedback but as a character flaw requiring correction.

These younger professionals have often been exposed to different organizational models—flatter hierarchies, cultures of psychological safety where dissent is encouraged, feedback systems that flow in multiple directions. They have absorbed, consciously or not, the language of contemporary management: authenticity, purpose-driven work, work-life integration, collaborative leadership. When they encounter organizations still operating on family-system dynamics, the cognitive dissonance can be profound.

What makes this particularly painful is that many of these young professionals deeply value their cultural heritage and family bonds. They are not wholesale rejecting Middle Eastern culture in favor of Western individualism. Rather, they are experiencing the difficult work of trying to integrate different value systems—honoring family while claiming personal autonomy, respecting tradition while embracing change, maintaining connection while establishing boundaries. The workplace becomes yet another arena where this internal struggle must be negotiated.

Senior leaders, meanwhile, often interpret younger employees’ expectations as entitlement, impatience, or insufficient respect. They see young people who expect rapid advancement without “paying their dues,” who question decisions without understanding the full context, who prioritize personal fulfillment over organizational loyalty. From their perspective, these attitudes reflect a troubling erosion of values that once held society together. The family patterns that shaped their own success now seem under assault.

This mutual incomprehension can create organizational paralysis. Younger employees become cynical and disengaged, viewing senior leadership as out of touch and resistant to necessary change. Senior leaders become defensive and rigid, doubling down on traditional authority structures precisely because they feel threatened. The organization fractures along generational lines, with each cohort reinforcing the other’s worst suspicions.

Yet this generational tension also contains the seeds of transformation. It makes visible patterns that were previously invisible, forces conversations that were previously avoided, and creates pressure for change that cannot easily be dismissed as coming from “outside” the culture. The question is whether organizations can harness this tension constructively rather than allowing it to calcify into permanent conflict.

Toward a Different Kind of Leadership

According to El-Orabi, recognition is the necessary first step toward change. Leaders must become aware of the family patterns they carry and how these patterns shape their behavior in organizational contexts. This requires a kind of psychological literacy that is not typically part of leadership development—an ability to reflect on one’s own emotional history and to recognize how unconscious loyalties and unexamined assumptions continue to operate.

What might leadership look like if it were freed from the compulsion to repeat these inherited patterns?

Following in the footsteps of Manfred Kets de Vries and others, El-Orabi contents that this process would begin with a fundamental reconceptualization of leadership itself—not as a form of domination but as an act of “containment.”

Under this new rubric, the leader would serve as a vessel to absorb, process and manage the anxieties, fears, and complex emotions within an organization, particularly in times of uncertainty. By embodying and creating safe psychological spaces—these containers—ideas and emotions can be expressed and processed, and ultimately transformed into clear direction and productive action.

Drawing from the work of Kets de Vries and others, El-Orabi describes the key characteristics of this new leadership model as follows:

Holding Anxiety: The primary role of the leader is to tolerate the system’s anxiety and tension without immediately trying to discharge it with premature reassurance or control. This means staying calm and grounded even in the face of pressure or chaos.

Metabolizing Emotions: Leaders absorb these “raw” emotions and transform them into something that can be thought about and acted upon. They convert fear and confusion into clarity and a set of choices for the team.

Creating Psychological Safety: The leader establishes the values, norms, and boundaries that create an environment of trust and safety, allowing team members to express themselves, share ideas, and engage in constructive conflict without fear of judgment.

Facilitating Sensemaking: By “holding the space,” the leader allows the group to explore different perspectives and make sense of complex situations together. This enables the group to work through challenges rather than fall apart under pressure.

Empowering Growth: The ultimate goal is to help individuals develop their own capacity for self-responsibility and maturity, eventually enabling them to manage their own “internal container”.

Conclusion: The Work Ahead

As El-Orabi explains, the transformation of Middle Eastern organizations is not primarily a technical or structural challenge but a psychological and cultural one. It requires that we become aware of patterns we have inherited, that we examine the unconscious loyalties that shape our behavior, and that we learn to distinguish between the authority that enables growth and the domination that stifles it.

This is difficult work. It requires us to revisit experiences that may be painful, to acknowledge ways we may have been harmed and ways we may be harming others, and to risk creating new patterns without the security of familiar templates. It means having conversations that Middle Eastern cultures, with their emphasis on harmony and respect for authority, have traditionally avoided.

Yet the urgency of this work has never been greater. As the region confronts unprecedented challenges—economic transitions, generational shifts, geopolitical instability—its organizations will need every ounce of creativity, commitment, and collaborative capacity they can muster. That potential will remain locked as long as workplaces continue to function as extensions of authoritarian family systems rather than as spaces for genuine human development.

The generational divide, uncomfortable as it is, offers an opportunity. It creates a productive tension that can catalyze change if organizations can learn to harness it constructively. Younger professionals bring fresh perspectives and legitimate demands for more humane, effective ways of working. Senior leaders possess hard-won wisdom about navigating complexity and understanding context. The challenge is creating spaces where both forms of knowledge can be honored and integrated.

The question, ultimately, is whether we can learn to lead differently—to transform authority from an instrument of control into what it might truly become: a commitment to creating conditions where others can flourish, think freely, and contribute their full humanity to shared endeavors.

The answer will shape not only the future of Middle Eastern organizations but the life possibilities of millions who work within them. The work is hard, but it is also hopeful: every moment of awareness, every small act of leading differently, every conversation that names what has been unspoken serves as a building block for this transformation.

The research discussed is based on Ahmed El-Orabi’s thesis “Egypt on Mind: The Role of Leadership Absence & Identity Fragmentation in Collective Social Anxiety and Defences” completed in 2025 as part of INSEAD’s prestigious Executive Master in Change programme.

References and Further Reading

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. Heinemann.

Bion, W. R. (1961). Experiences in groups: And other papers. Tavistock.

El-Orabi, Ahmed (2025). Egypt on mind: The role of leadership absence & identity fragmentation in collective social anxiety and defences [Master’s thesis]. Executive Master in Change, INSEAD.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2001). The leadership mystique: A user’s manual for the human enterprise. Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2006). The leader on the couch: A clinical approach to changing people and organizations. Jossey-Bass.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R., Korotov, K., & Florent-Treacy, E. (Eds.). (2007). The coach and the leader: International perspectives on executive coaching. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2014). Mindful leadership coaching: Journeys into the interior. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R., & Cheak, A. (2016). Psychodynamic approaches to leadership development. In G. R. Goethals, S. T. Allison, R. M. Kramer, & D. M. Messick (Eds.), Conceptions of leadership: Enduring ideas and emerging insights (pp. 65–82). Palgrave Macmillan.

Scharmer, O. C. (2009). Theory U: Learning from the future as it emerges. Berrett-Koehler.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Volkan, V. D. (1997). Bloodlines: From ethnic pride to ethnic terrorism. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Volkan, V. D. (2001). Transgenerational transmissions and chosen traumas: An aspect of large-group identity. Group Analysis, 34(1), 79-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/05333160122077730

Volkan, V. D. (2004). Blind trust: Large groups and their leaders in times of crisis and terror. Pitchstone Publishing.

Volkan, V. D. (2006). Killing in the name of identity: A study of bloody conflicts. Pitchstone Publishing.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment: Studies in the theory of emotional development. International Universities Press.