Writer on the Couch: 'In the end, writing has kept me sane.'

A Conversation with Manfred Kets de Vries on Writing, Reflection & His Own Inner Theatre

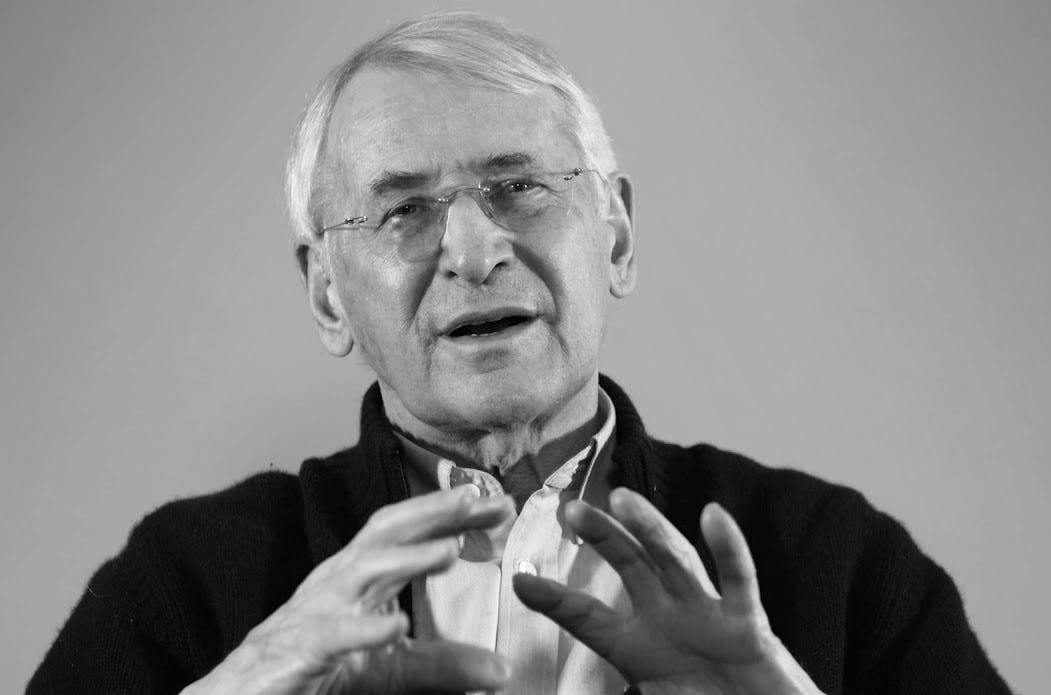

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many leaders and scholars were retracting, regrouping—simply trying to find their bearings—Manfred Kets de Vries, a trained psychoanalyst, scholar and renowned expert on the psychology of leadership, had his most prolific writing period ever. And this is saying a lot for a man who has over 50 books and 400 articles to his name.

Publishing a jaw-dropping eight books between 2020 and 2022, Kets de Vries took on subjects ranging from the existential challenges of authentic leadership to the narcotic lure of such narcissists as Trump and Putin.

In short, while others paused, Ket de Vries pulled few punches.

A partial list of those titles speaks to both the universality of his themes, and their timely import: Leadership Unhinged: Essays on the Ugly, the Bad, and the Weird, Quo Vadis? The Existential Challenges of Leadership, and Leading Wisely: Becoming a Reflective Leader in Turbulent Times.

But when asked in a recent conversation how he was able to pull this off, Kets de Vries seemed mildly amused and oddly astonished at himself. “It’s crazy!” he replied, shaking his head and laughing. But then he added, without skipping a beat:

“Writing has kept me sane. It has become my own therapy”.

Writing, during this period and throughout his professional life, has allowed Kets de Vries to do two things: 1) grow as a thinker able to engage an audience far wider than that of the typical academic, and 2), reflect on the callings of his inner theatre in what could be termed the ‘safe space of writing’.

As the Distinguished Clinical Professor of Leadership Development and Organisational Change at INSEAD and the founder of the Kets de Vries Institute, he is certainly no stranger to the demands of professional life. Yet somehow, he has managed to craft a path for self-reflection, growth, and professional enhancement—through writing

But how has he been able to do this? And what are his deeper motivations?

Reflection and the Writing Life

When asked where this inner calling comes from, Kets de Vries pauses to reflect and then explains:

Somebody once told me, if I don't play the piano daily, I don't feel well. Writing functions in a similar way for me. If I don't write, I don't feel well. So, if I write a number of hours a day, I feel that was a good day. Now… my writing for that day might be garbage, but still the act of writing… my effort to get some words on paper … is certainly important for my mental health.

In line with the science of prolific writing which draws both from psychology and mind-body practices, Kets de Vries’ writing life is largely generated by habit. A near daily practice that sustains him through the ups-and-downs.

It typically takes place in one of his two residences: his apartment in Paris or his farmhouse located up a hill outside Grasse. During much of the early years of COVID-19 pandemic, it was to his farmhouse that he retreated, finding there a setting particularly welcoming to his writing:

When the pandemic hit and we all had to go into quarantine, I suddenly realized how much I traveled, how many conferences I gave, and how much I taught … and, in general, all the time I could have spent on writing instead. There were no vaccinations at the time, so I was basically forced to hide somewhere, which turned out to be my house in the south of France.

There I often found myself spending time sitting on the terrace looking out onto our large garden, watching the birds, and listening to the sounds of nature. Sometimes out from the little forest in the back a wild boar or a roebuck would appear. And that was quite inspirational. But, yes, I was stuck. I couldn't go anywhere else. That might have been part of why my writing took off exponentially…

As his writing habit has grown and become instilled in his life, he has come to discern the best time for this ritual:

I pay attention to my natural biorhythm. I am a lark. You know, they say that you are either a lark or an owl, right? I am that lark—a morning person. I know my best time to write, which is when the morning light hits. That is dependent on the season. For example, in the spring and summer, I get up much earlier. I could rise and write from say five to ten, but now in the winter, it's much later, so from maybe seven to eleven or something like that. But I know that at most I have three hours in me. Three hours, that's it. After that, I begin to fidget.

Sometimes, “Pure Garbage”

But what emerges in those three hours is less the point, than putting in the time, engaging the process, and allowing what comes to come—in ways, not unlike therapy. Kets de Vries elaborates, beginning with some tips for those who may be caught in a cycle of procrastination:

… if you are struggling to write, just decide to write any garbage. Don't be too self-critical. That's what I do, I write any garbage. Pure garbage. My first draft may be a mess, but then I tell myself that’s just my first one. So don't be intimidated by garbage. Tomorrow is another day.

Kets de Vries confirms what many know—good writing happens at the revision stage:

I have to say that with every sentence I write, I end up rewriting it probably at least 12-15 times. I keep on playing with it, and then as the final test, if I have the time, I read it out loud to myself, and then I know it's correct. So that's what I sometimes do, depending on if I’m in a hurry. But sometimes when I read it out loud, I must admit I can shock myself! How could I have written that?

The prolific writer then is often in conversation with the self, luring out the ideas and words, through a simple devotion to habit. The good comes. The bad comes. The shocking comes. And then there is another day.

Kets de Vries points out that ideas must sometime be coaxed. At other times, they emerge spontaneously, when the setting is right. A hot bath can even serve as such a setting:

Let me say that I like bathtubs! I don’t like showers the same way. Of course, I take showers, but I do prefer a bathtub. And I make the water hot — quite hot! There I will sit and my mind starts to float. And then what I’m writing often comes to me and I get ideas. In that floating, relaxed state of mind.

Getting away from the desk or computer, too, has its own way of rejuvenating the writer’s mind. He explains:

Not so much here at my Paris apartment, but when I am in the south of France, I try to walk every day in the forest and around. And ideas will come to me naturally. I might start to think that this could be included or I could look at that.

Setting aside judgement and embracing a faith in tomorrow, as well as in the process itself, seem integral to the sustained writing process. Kets de Vries continues:

I'm writing an article at the moment on populism. I know it's not structured properly and I'm struggling with it, but I know tomorrow is another day. Tomorrow I will likely feel better. And some ideas will come to me. But it’s true—at the end of a writing spell, I can sometimes feel disgusted with myself. I feel what the hell have I done? But then the next morning, bang! I have some new energy and look at it again and I start to tinker with it.

The writer holds a vision of what is possible, something he or she feels must be said—though the way there is yet unclear. The habit, the process, a caring for the full self—mind & body—create a fertile ground for that vision to emerge.

Still a steadiness is required. A willingness to stay the course.

An Interloper in the World of English

As hard as it is to believe, one of the Kets de Vries’ insecurities as a writer is related to what he described as this “lingering sense that my English is off”. With Dutch as his first language and German his second, English is not his native tongue. Yet his contribution in the language is indisputable—some 50 books and 400 articles, along his own series at Palgrave Macmillan.

Still, he insists, English remains something of a “foreign” territory for him. A place where, somehow, he feels he does not have full citizenship. An interloper. He speculates about where this comes from:

Yes, even today, I feel this insecurity about English. It’s interesting. I think about my mother who probably had a hidden desire to be a writer. She was brought up in Germany, but she was Dutch so her Dutch was never perfect. There were always imperfections, and she would sometimes create words out of German when speaking Dutch. Strange words. As a kid, I remember seeing her use those kinds of words and I was embarrassed about it. I think I’ve incorporated a part of her in me.

Incorporated within Kets de Vries, he explains, is this part of his mother—a woman who may have dreamed to a writer, but who was also something of a stranger in her own land—at the very least, linguistically.

Yet, as he continues, it becomes apparent that there was much more to her than that.

She was a woman able to adroitly manipulate the line between her German and Dutch identities in an effort to bypass the terrifying measures imposed by her Nazi occupiers. She was, most clearly, a force to be reckoned with.

In Part II of “Writer on the Coach: Little Manfred & the Bull”, we explore Kets de Vries early life, the Nazi resistance work of his mother and grandparents, his Jewish father’s own “resistance,” and how these themes continue to influence his writing.